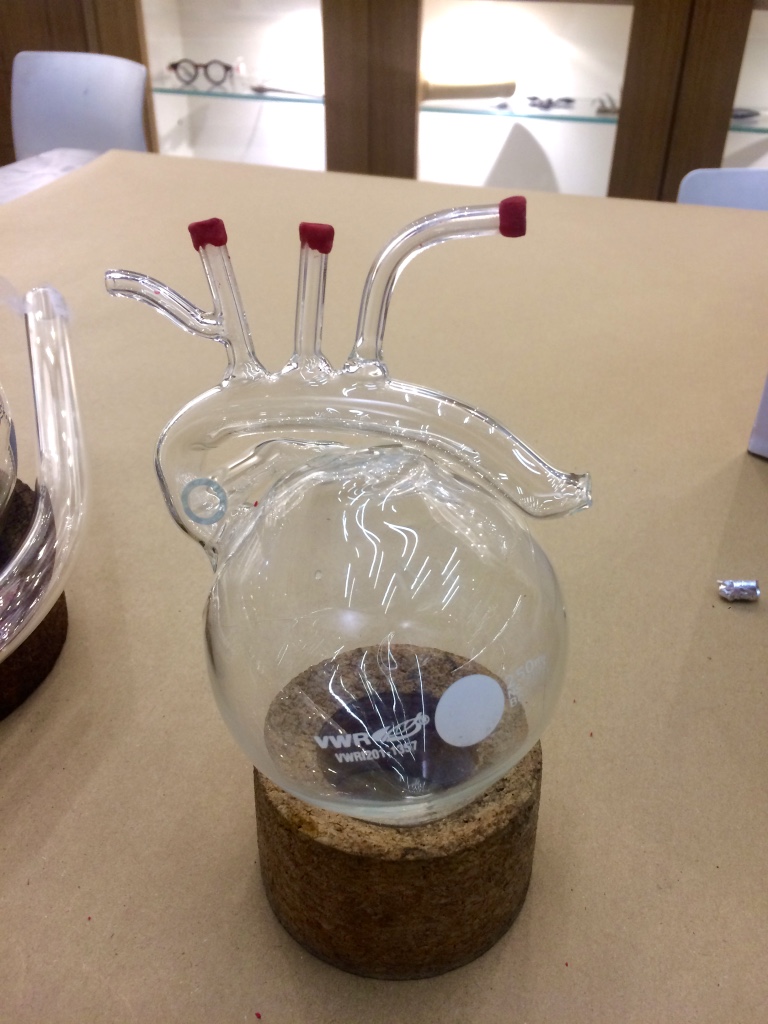

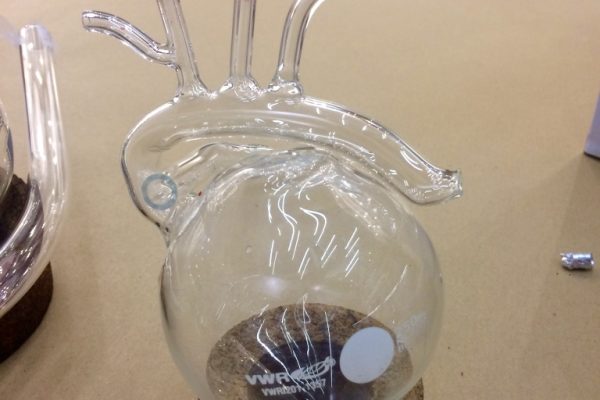

For the interdisciplinary colloquium on GOLD at the Institute of Advanced Study, UCL, and then at the Royal Institution, I made a presentation entitled Gold as a Human Barometer, alongside two blown scientific glass objects in the form of human internal organs.

We love gold’s reflected light, its mellow persuadability, and its non-reactivity in the body. Gold is inert.

Or is it? Gold behaves entirely differently on the nano-scale, its active properties range from optical and electronic to antimicrobial and biosensory, carrying antibodies through blood plasma. Smart nanoparticles combine functions of targeting, imaging and drug delivery. Far from being inert, gold is a versatile actor: a sensor, lens and agent of transformation in the body.

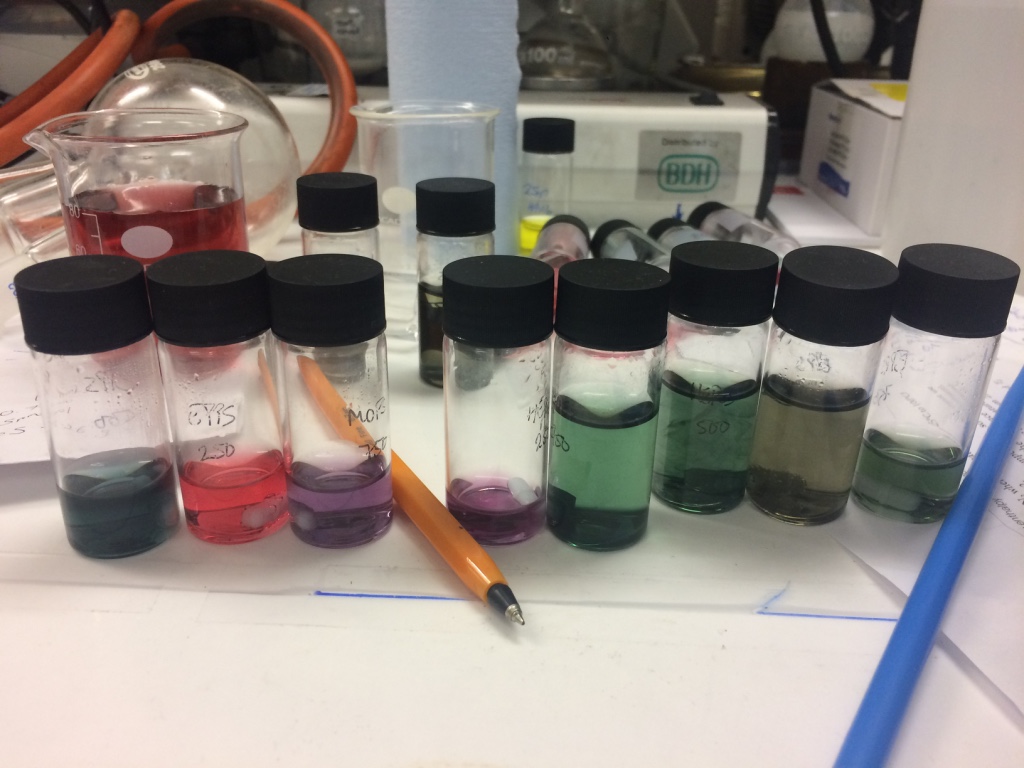

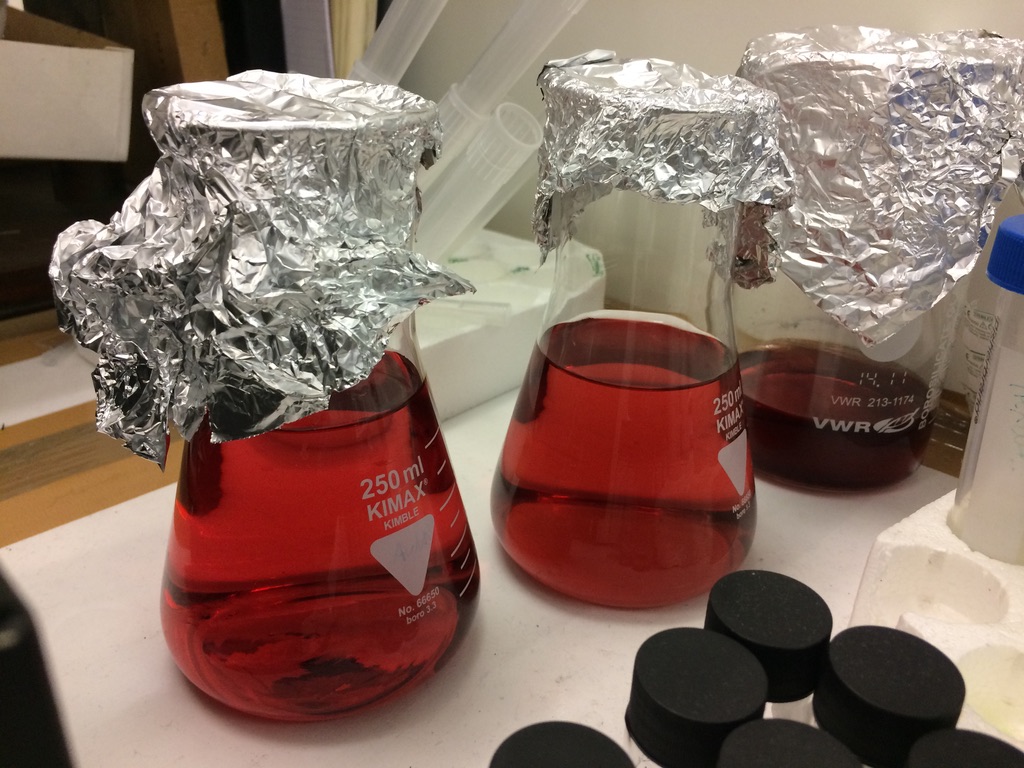

The link between gold and the blood does not end there. Alchemists knew how to use it to ‘stain’ glass blood-red even if they didn’t attribute it to nanoparticles. Faraday recognised that ‘activated gold’ would absorb and scatter light, producing a moody rainbow of reds, purples, browns and blues according to particle size.

Hooke’s early weather instruments were tinted ‘the lovely colour of cochineal’, using kermes, dragons blood or red wine spirits. The link between the behaviour of the liquid in the weather glass and the swirl of human feeling was well developed in the 18th century, backed up by a host of scientific and pseudoscientific theories.

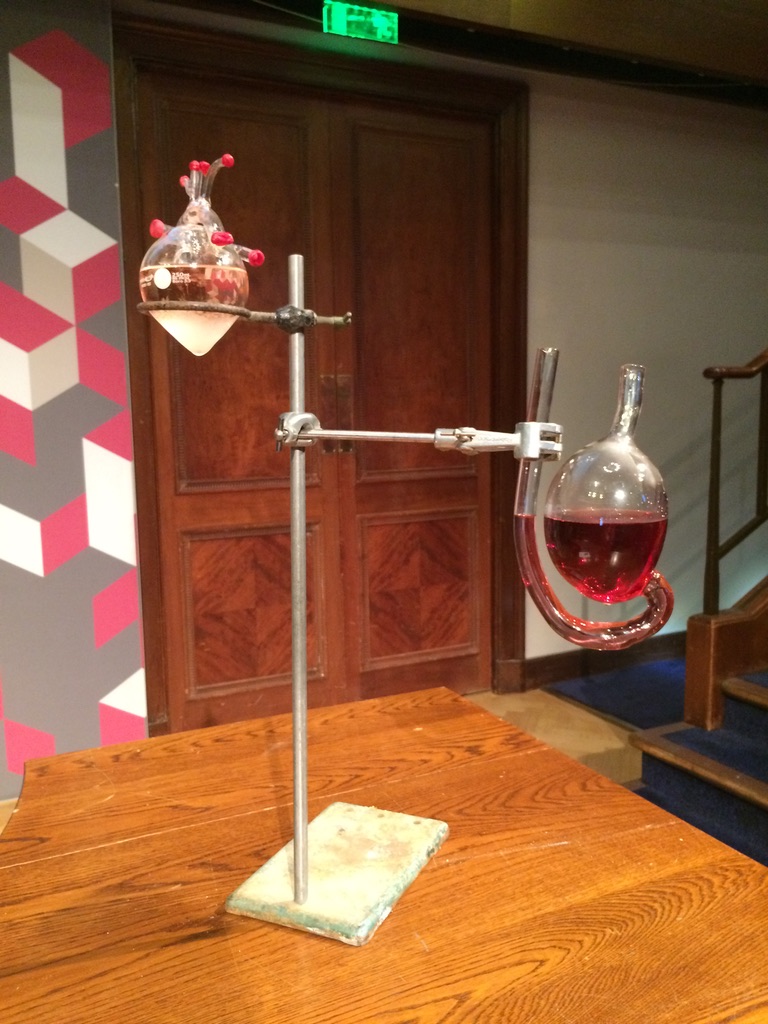

If colloidal gold is an agent of change in the body, can it take our emotional temperature? Mirror how we are? Driven by ideas from the history of science, modern materials science and biochemistry, these experimental barometers bring together temper and temperament, gold, glass, wine, light, transubstantiation, ingestion, emotion and the body to raise questions about the enmeshment of human and non-human matter.

Through the barometers, I was able to see how materials, particularly metals, work in and out of the body, the way materials work with light, and how they behave and can be used by our bodies and by medicine. They can act and are valued entirely differently depending on the scales at which they enter the body. The barometers also ‘measure’ or refer to mood, emotion or temper.

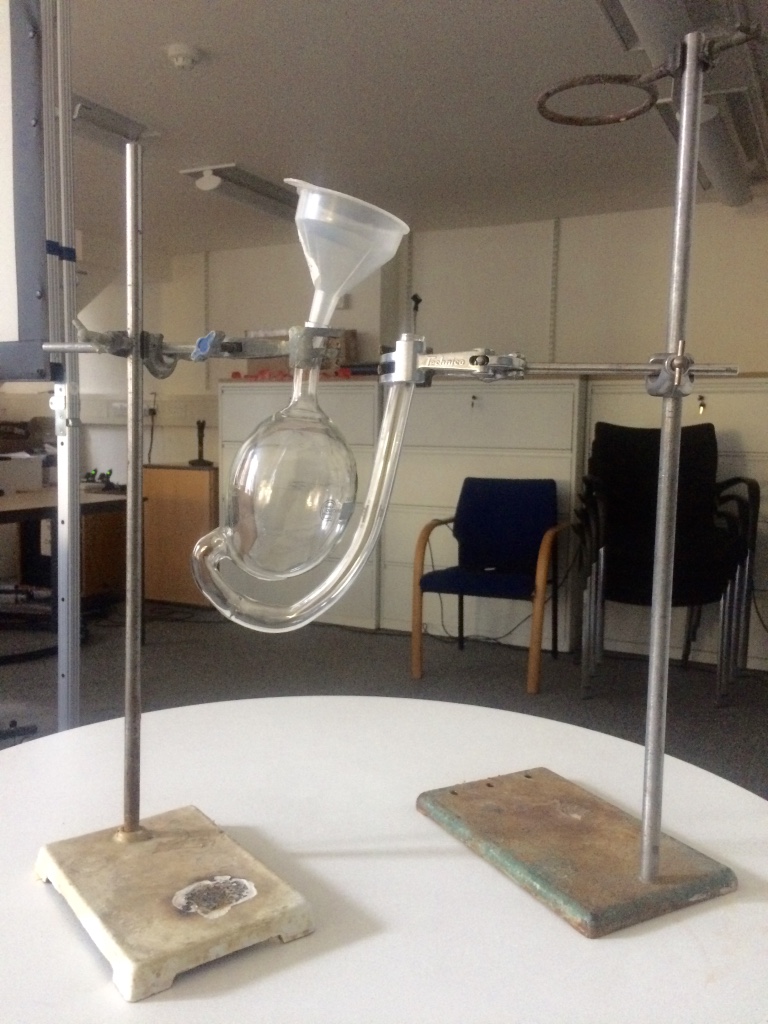

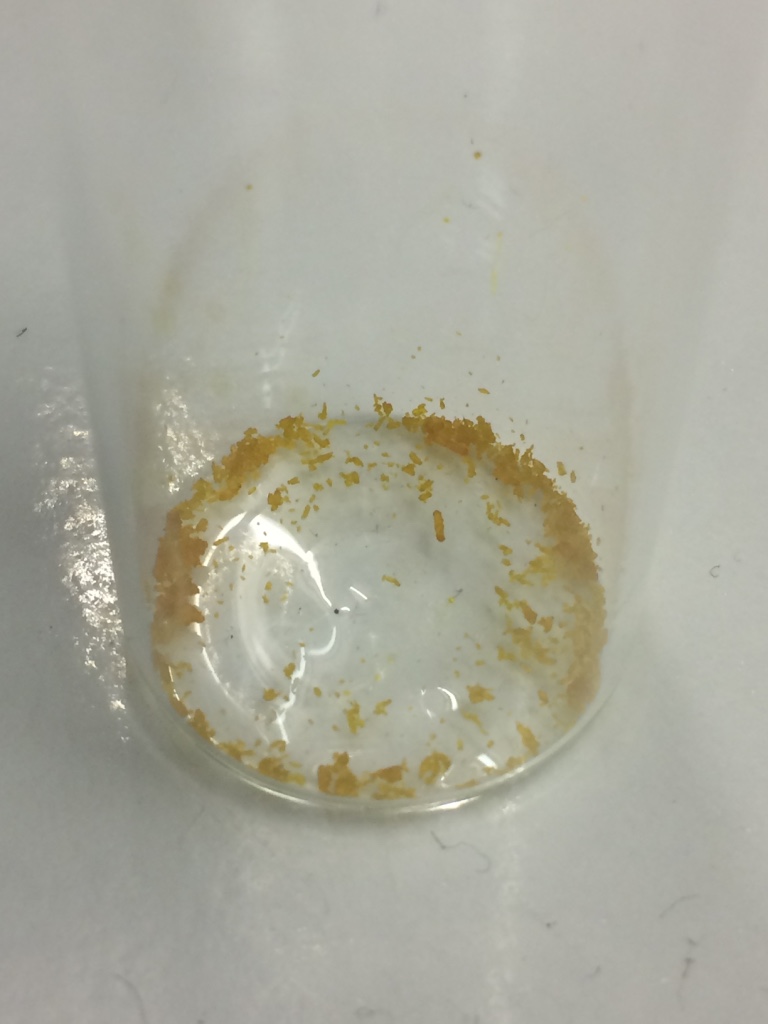

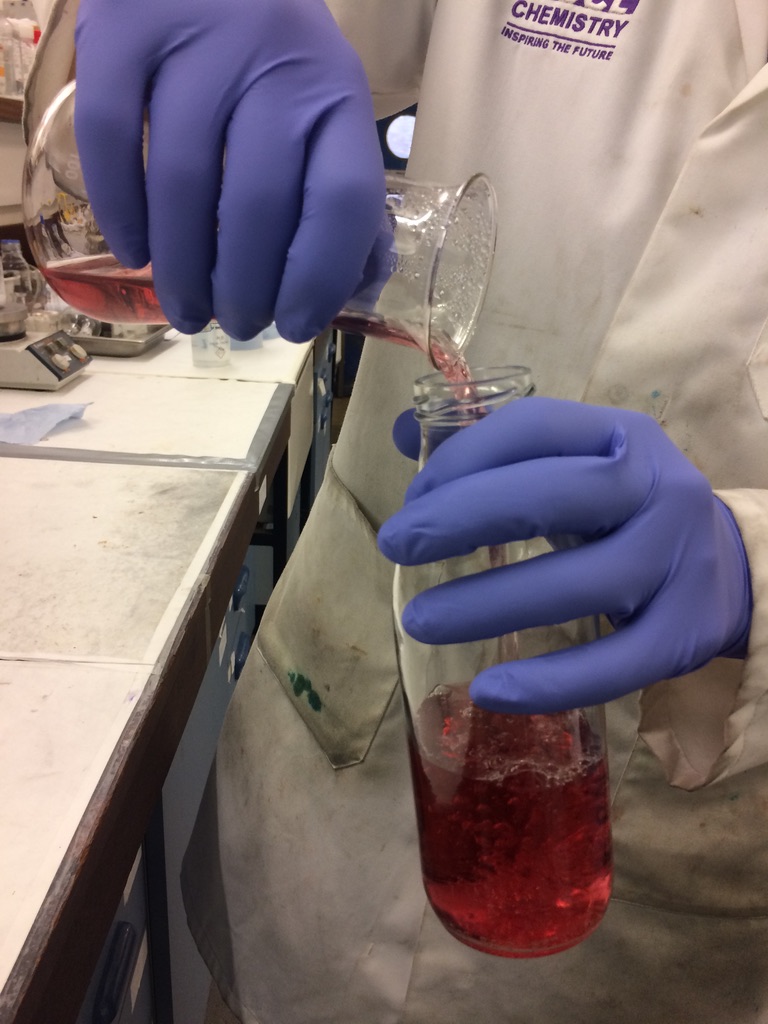

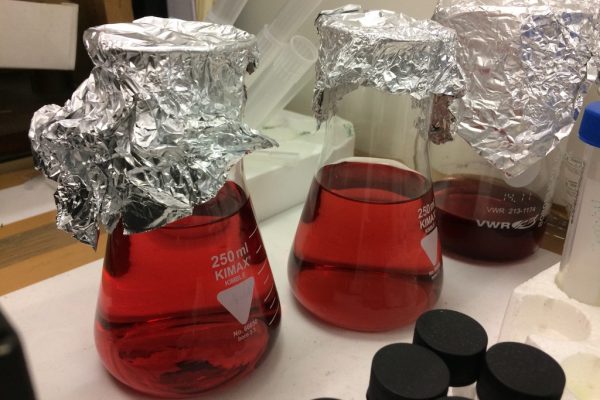

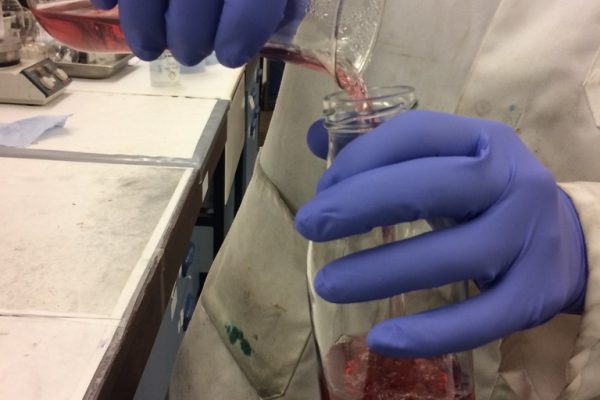

These were made with John Cowley, UCL Chemistry’s resident glassblower, both working barometers. The stomach contained red gold nanoparticle colloidal solution to imitate the ‘spirits of wine’ used in historical barometers, and one contained a saturated camphor solution which is in a constant state of crystallisation which waxes and wanes with the speed of atmospheric temperature changes. The colloidal solution was made with Tom MacDonald, a research fellow in nanotechnology and materials chemistry at UCL.

Working with glass makes clear the way that treatment affects structure, and structure affects behaviour. Glass needs to be tempered, it needs to be cooled very slowly for it to survive and you can utterly change its behaviour or performance by heating or cooling. Using gold, glass and light in these barometers brings about a kind of imaginative transubstantiation, a mutable instrument of material temper and human temperament.

How do our bodies change with our environment? Joints ache when it rains, fingers crisp like seaweed, we begin to store fat for winter.

Thanks to Dr Hannah Drayson for sparking the beginnings of this work with me back in 2012